There are approximately 1 .3 million snowmobile households in the United States. Of that number perhaps .3 million know how to properly care for their sled. That leaves an estimated one million persons who are not all that keenly aware of the machine in which they’ve invested a substantial amount.

Most of the snowmobiling public may not recognize a coil-over-shock from an idler wheel. For that matter, things which make up the rear suspension of a sled may commonly be referred to as a thiga-ma-gig or some other make-shift term. For that matter, the function of a suspension or a part of a suspension may be totally unknown to an owner. (Try ordering a thiga-ma-gig, it’s not only difficult, it’s impossible)!

It’s not all that difficult, however, to comprehend the components of that 1979 sled that’s just been uncrated in the garage if time is taken to associate various sled parts with their proper function. That means of course, that one will have to give up on calling things thiga-ma-gigs and do-dads, but then performance of the machine might be a worthwhile cause.

Most long travel rear suspensions are not all that complex in today’s refined machines, giving owners fewer parts to learn and fewer headaches on the trail. The most impressive innovative Step in snowmobile rear suspensions has been the long travel feature. It is a suspension, as the term implies, which sports long, extended travel (generally, the distance which the track travels from the tunnel to the ground), varying in distance and point of measurement from one manufacturer to another.

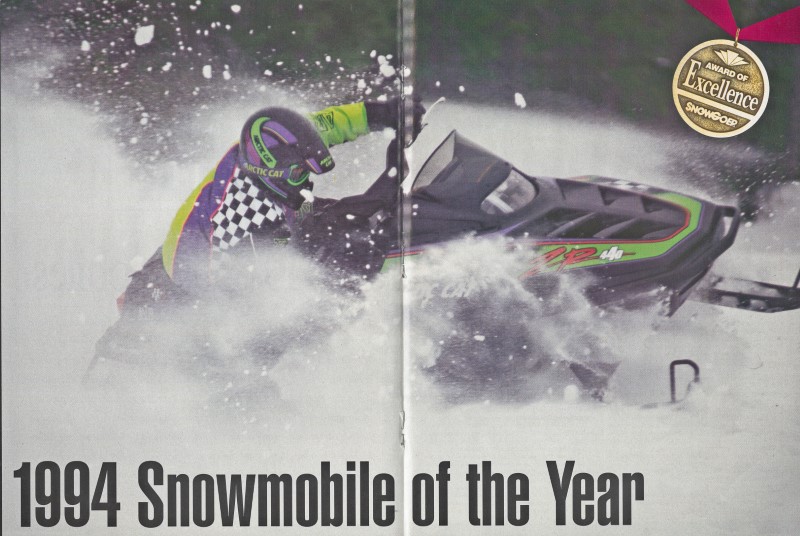

Today’s sled suspensions vary from Kawasaki’s four inches to Arctic Cat’s seven inches on stock sleds, depending on the manufacturer’s refinement and definition of the distance traveled.

For example, Arctic Cat’s new Trail Cat has the longest travel, seven inches, on the market. It should be noted that the length of travel is not necessarily the foremost facet of a sled’s riding capabilities, but rather, it serves as a means of defining how much extension a suspension has, that’s all. Ride is measured by a rider’s acceptance or non-acceptance of a sled’s riding comfort.

A machine by machine, manufacturer by manufacturer breakdown of long travel rear suspension sleds lends some insight into the anatomy of the newest form of rear suspensions.

Trail Cat is new all over. New for the 1979 model year, sporting the independent front suspension, Trail Cat is the rave of the industry. It’s suggested, however, not to fixate on the front of the machine, because the rear long travel suspension, with its seven inches of travel, will be just as intriguing. “Under normal conditions there is a drop of three inches, and a collapse of four inches,” said Gene Hanson, senior project engineer for Arctic Enterprises, “with the first three inches dropping when the rider is seated on the sled.” Hanson noted that due to increased travel, the Trail Cat sits higher than other, more conventional sleds, allowing for a smoother ride and increased rear suspension travel.

Trail Cat’s rear arm assembly attaches to the rear axle, a hex shaft is used to transfer the torque from the rear arm assembly to the forged aluminum shock arm assembly. The shock arm is attached to the coil- over-shock on the side of the sled’s chassis. The cam adjustable shock is covered by a plastic cap to keep fingers and debris out of the spring and shock unit.

(A “sit in” feeling resulting from a higher stance offers tall riders a more comfortable riding position).

In addition to the absorbing function, Arctic’s shocks serve as limiters, and the rubber stops on the shocks are compression limiters. (The extrusion stop is built into the shock absorber, serving as a stop in either direction of the shock’s motion).

The front assembly arm torsion spring, designed with a shock assembly connected to the rail, compensates for difference in lost motion, which makes the front of the suspension independent of the rear portion. Most of the weight is on the rear portion of the suspension, thus, the front arm has somewhat less than seven inches of travel.

Trail Cat’s luxurious eight inch seat is featured as an integral part of the sled’s rear suspension.

Nineteen-seventy-nine is Polaris’ first year with long travel rear suspension on a stock sled. The all new Centurion, a three cylinder screamer, moves into the spotlight with something other than maximum horsepower. Six inches of travel from the base of the rear torque arm to the rubber bumper at the base of the slide rail offers Polaris Centurion owners a ride par excellence!

The increased travel is double that of previous models, and offers an increased spring rate to eight inches, with a less aggressive spring, which results in a better overall ride over those rough, bone-jarring trails. The increased number of loops in each spring broadens the base on which the ride is cushioned.

There is less shock control in this year’s Polaris which means the shock will work well even under extremely cold conditions. Therefore, the shock oil is not forced to travel through the small orifice, which lends itself to more travel and equals less effect on the shock rate and lessens the frequency of bottoming out.

This year’s suspension weighs about 12 pounds less than last year’s offering, and is much less complex. Polaris simplified it without sidestepping performance and reliability. This lighter suspension was brought about by utilizing more aluminum and less steel.

Polaris moved the four rear idler wheels farther apart, which means twice the surface holding alignment. Realignment means the idlers are under less individual stress, which reduces breakage. An additional benefit of the new wheel alignment is the decreased amount of track bowing. The two center wheels serve to hold the track alignment secure.

Adjusting the track on the new Polaris long travel rear suspension is simplified by placing back bracket adjustment bolts outside of the rail for easier adjustment. Coil springs are also adjustable to allow for variation in travel of the torsion springs, giving greater weight variation. Even the slightest adjustment is noticeable. Polaris not only increased the number of coils, but also increased the thickness of the wire, which improved the spring strength and cushioned Centurion’s ride.

Weight reduction is the most noticeable effort manufacturers are making, in Polaris’ case, the brackets are being constructed of high strength aluminum rather than steel.

Centurion’s front torque arm is easily adjusted by raising or lowering the shock angle — the steeper the shock angle the more cushioned the ride will become. (The lower hole is for heavy riders or rough terrain). In keeping with the overall lighter weight design of the suspension, the front torque arm is less complicated this year, with fewer components to make up a strong sled suspension.

The Polaris limiter strap is adjustable, as well, in controlling travel of the front torque arm. In past Polaris models this strap was made of steel which caused excessive clattering. This year the limiter is made of belting.

The front shock, which replaced two coil springs, is fully adjustable with the wrench provided with each sled. One great advantage most sleds offer is the ease with which rear suspensions are removed for working on the unit. Four bolts in the chassis release the suspension when removed.

“We don’t consider this the optimum in long travel rear suspension, it’s an increase for us over the conventional rear suspensions of about 2-to-1, which helps us improve our ride,” said Dick Teal, John Deere’s project engineer in charge of the new Trailfire. “Our travel was about 2% inches to 21/2 inches on our old sleds, but our new suspensions boast about five inches from the track to the top of the tunnel, measuring the movement of the rear wheels.” (It’s 6.01 inches from the track to the top of the tunnel). The front portion of the suspension carries most of the sled and passenger weight by design. Sixty per cent of the weight is behind the point where the hyfax first touches the ground, with the other 40 per cent of the weight placed on the skis.

Shocking on the all new Trailfire is accomplished through computer analysis, which determines the size of the shock, thickness of the spring wire and so on. This allows for quicker designing of suspensions, and eliminates a lot of trial-and-error time. All springs and spring rates are then determined by ride testing to establish the feasibility of spring weights after the computer has designated the spring type. This allows for the human touch and verifies the choice of the springs used.

Teal said Deere’s attempt to increase the suspension travel on consumer sleds is an attempt at increased comfort at a minimal cost to Deere and its customers. In designing the suspension, Deere kept the number of pieces in the unit to a minimum, which allows snow to move freely through the suspension, eliminating ice build-up and provides adequate cooling to the ultra high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMW or hyfax).

Deere’s front swing arm is made of box steel tubing which carries two springs. The springs have two adjustments for heavy and light operators. Movement of the rear swing arm is tied into the front with a shock, thus weight is distributed evenly over the entire suspension.

Removing Trailfire’s suspension is accomplished by removing four bolts in the tunnel. Almost as easy to remove is the hyfax. Simply remove the bolts on the front of the rail and slide the hyfax out through the back of the track — there is no need to remove the track to complete this task.

John Deere’s patented seat design is made of a minimum of eight inches of thick foam, three layers deep. Tapering from the driver area, the foam is brought to a height of 9.2 inches in the rear passenger area, The seat cover is loosely fitted to allow the cover to breathe. The foam retains more air, therefore, maximum cushioning is realized, especially over rough terrain. Quick rebounding is the primary feature of the seat’s suspension capabilities.

Deflection of the rear idler wheels to the rail is five and one-half inches on Scorpion’s Whip TK. The conventional travel is 4½ inches metal- to-metal. The change was initiated by Scorpion to provide an improved ride.

Scorpion uses a spring overshock which is anchored ahead of the front pivot point, so the rear portion of the suspension will interact with the front portion of the suspension. When the rear portion is engaged it causes a retarded pitch and keeps the front of the suspension on the ground at impact. This method of absorbing impact promotes a flatter ride and eliminates pitching.

The rear idler wheels, two five-inch wheels, are adjustable to maintain proper track tension. Two upper idlers serve to guide the track and maintain correct track tension when the suspension is compressed. Adjustment is made by tightening two bolts at the rear of the suspension unit.

Scorpion’s use of aluminum and steel in their Para-Slide II suspension combines to lighten overall sled weight. Simplicity has been designed into the suspension and eliminates snow and ice build-up.

Another improvisation Scorpion engineering chose to use was a solid, rather than “I”- shaped, rail for increased strength and elimination of ice build up on the slides.

The Scorpion shock is a four position adjustable shock, preset to its lightest setting. Each position increases the preload by 25 pounds as it is tightened. Most persons operate their sled on the first or second setting.

The front springs are not considered as primary load carrying springs, therefore, they are not set to carry as much preload. Instead, the front springs serve as limiters, which eliminates the necessity for additional straps or hardware.

Scorpion’s idlers are designed to reduce friction on hard pack or ice. They are constructed to carry the weight of the sled and rider, removing all weight from the rail and hyfax.

Bombardier’s rear suspension, complete with ground leveler, has a travel of 4½ inches from the ground to the chassis. The suspension, first used on the Everest, is standard on all Bombardier machines with the exception of the Elan and Alpine.

The torque reaction system, as it is called, is used by most of the snowmobile industry. It is made of extruded aluminum with a single shock used to cushion the ride. The old system was made of mild steels which were heavy and bulky. Sprockets have been replaced by idler wheels, for greater simplicity and easier replacement.

Torque reaction, derived from the engine causing a direct drive to the track in a forward motion causes the front arm to move horizontally, according to Phil Mickelson, service manager at Bombardier Corporation, Duluth, Minn. A simple adjustment to the front limiter strap allows for the front portion of the rear suspension to lighten up and puts the weight on the rear axle. For mountain riding the strap, for example, should be fully extended, and heavier springs installed in the front, which help the sled stay on top of the deep snow.

Bombardier’s shock has a primary function of dampening impact, and a secondary function of limiting travel. The springs are adjustable to suit the weight of the driver.

A simple adjustment of two bolts gives the track the desired tension. The proper tension is maintained in spite of terrain variations by the constant compensation of the torque arm and rear top idlers. Thus, there should never be a loss of horsepower.

Each axle of Bombardier’s stock sled is adjustable independent of the other, giving the rider the freedom to suit his particular driving condition. The rear springs are adjusted to the amount of weight the sled is to carry. However, in powder snow it should be adjusted to the stiffest degree, with powder snow serving to cushion the ride to a great extent.

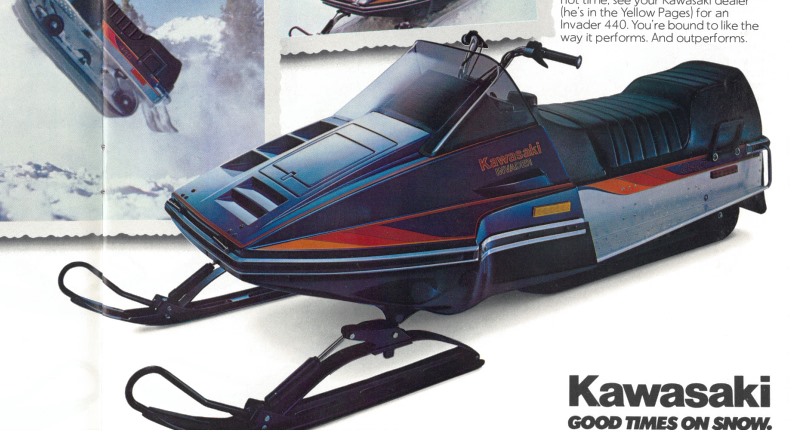

The newest manufacturer in the market, Kawasaki, equips its sleds with four inches of travel in their rear suspensions. The key to the travel has been with the bendable suspension. That is, Kawasaki’s rear idler arm is constructed in two “bendable” segments, which flex on impact. (See photo). Kawasaki engineers designed the spring- over-shock to ride on, NOT to absorb. The shock is completely adjustable, within limits, for a person’s weight. An optional two passenger spring set is available for families who ride double most of the time. (The sled was originally designed, however, with single passenger use in mind.)

Kawasaki sleds are developed to increase travel. However, the ski stance must also be increased to compensate for an increase in the rear suspension which will increase in height.

Future Kawasaki cross country sleds may increase the amount of travel to 8 inches, but the consumer sleds will maximize at between 5 and 6 inches of rear suspension travel, Kawasaki engineers said. Long travel suspensions have brought with them a required redesigning of the tunnel in order to compensate for the idler wheels and vertical track travel.

Long travel suspensions have introduced increased riding comfort, a modified suspension, and simplicity.

Captions

1. Arctic Cat implements the same rear suspension on their new Trail Cat as found on the Jag series. However, there are some very important changes. Perhaps one of the most noticeable variations is the coil-over- shock units mounted on either side of the tunnel. Each shock unit is covered with a plastic protector to keep fingers and debris out. Trail Cat’s increased travel measures seven inches, making it the longest in the industry.

2. A rear view of Bombardier’s classic Torque Reaction rear suspension is the basis for most concepts of rear suspensions now being used in the snowmobile industry. Using three idler wheels rather than the sprockets of the “old days,” Bombardier has not only lightened the suspension, but has made the system less complex.

3. Polaris engineers utilize four rear idler wheels, designed to eliminate track bowing.

4. Rear overhead idlers, mounted on flexing rear torque arm, enable Polaris tracks to travel smoothly and maintain track thrust through all kinds of snow conditions.

5. Kawasaki rear suspensions boast four inches of travel. A key in designing the Kawasaki rear sUspension has been the use of “bendable” rear torque arms, which increases cushioning capabilities of the sled’s reaisuspension. Kawasaki engineers use three rear idler wheels to maintain track stability and proper tension.

6. A cam adjustable coil-over-shock is used to absorb the shock incurred by the rear portion of the suspension, result: Rider comfort is directly improved. The front torque arm, shown here in a collapsed position, is bolted to the tunnel as is the rear torque arm, permitting easy removal of the suspension.

7. An innovation used by Scorpion for ‘79 is the “tie-in” of the front and rear torque arm assemblies, which gives the rear suspension a “work together” effect.

8. Looking from the rear portion of the Trailfire’s suspension, simplicity is evident. Two idler wheels serve to carry the rubber track. The rear torque arm is bL.ilt for maximum strength and minimum weight. The rear shock absorber is mounted in a near vertical position, thus, the shock is able to absorb the maximum amount of impact.